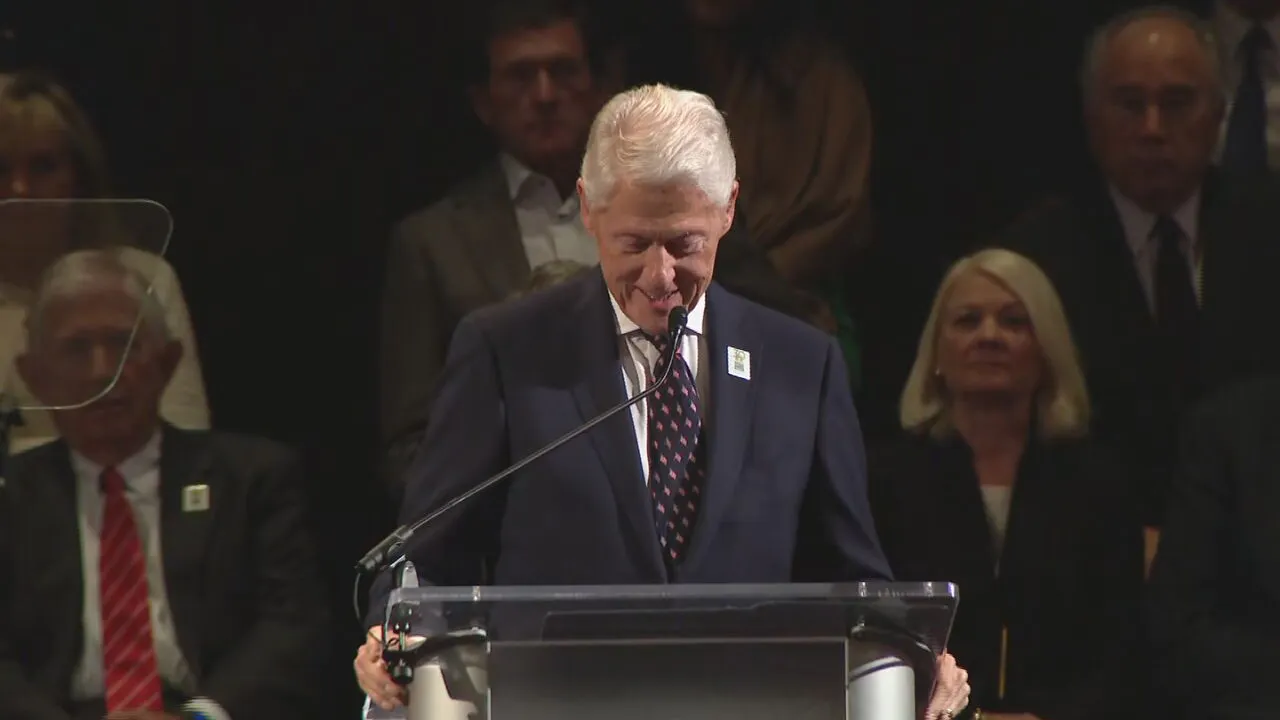

On a clear spring morning in Oklahoma City, where the echoes of loss and resilience still live in the shadow of the memorial gates, former President Bill Clinton returned to deliver a message to a nation still wrestling with old wounds and new divisions. The occasion was solemn but unifying, marking thirty years since the bombing of the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building—the deadliest domestic terrorist attack in American history.

Standing before survivors, families of victims, first responders, and a new generation that learned about April 19, 1995 through textbooks and documentaries, Clinton’s voice carried the wear of age and experience, but also the unmistakable strength of conviction.

"If our lives are going to be dominated by the effort to dominate people we disagree with, we’re going to put the 250-year-old march toward a more perfect union at risk," he said, his words cutting through the silence of remembrance like chimes in the wind.

It was not just a reflection on the past. It was a warning about the present.

Three decades ago, the nation had been shaken by an act so violent and calculated that it redefined the boundaries of fear. Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, fueled by anti-government extremism, parked a rental truck loaded with explosives outside a bustling federal building on a Wednesday morning.

Within seconds, 168 lives were gone, including 19 children in a daycare center. Nearly 700 others were injured. A city was devastated. A country was stunned.

But in the days that followed, amid the rubble and ruin, something extraordinary happened. Neighbors became family. Strangers became saviors. The people of Oklahoma City, joined by support from across the nation, embodied a resilience that would come to be known as the "Oklahoma Standard."

Clinton, who was president at the time of the attack, reflected on that very spirit during his speech.

"None of us would ever get much done. Believe me, we’ve all got something to be mad about, something legitimate to be mad about. You made a different decision," he told the gathered crowd, many of whom had lived through the horror and its aftermath.

He paused for a moment, allowing the weight of his words to settle. There was no need for elaborate rhetoric or political overtures. The gravity of the occasion spoke for itself.

"So, my advice to America today is, that we were there for you when you needed us," he continued. "America needs you, and America needs the ‘Oklahoma Standard,’ and if we all live by it, we’d be a lot better off."

The Oklahoma Standard was not a phrase created by a speechwriter or a branding team. It emerged from action. As former Oklahoma Governor Frank Keating once said, it was born of an "aggressively generous" community. People opened their homes, gave blood, shared food, stood in lines that stretched for hours simply to help.

In 1995, the world saw a new kind of American hero—not in uniform, not on the battlefield, but in every neighbor who stepped forward to serve. Clinton, ever the student of history and humanity, knew the power of that symbolism.

What made his message resonate even more deeply was its relevance in today’s political climate. The divisions across the country have grown sharper in recent years, not just in Washington but on streets, screens, and dinner tables.

The language of disagreement has become hostile, and the space for common ground has shrunk. Clinton’s call to unity was not just ceremonial. It was necessary.

"America needs you," he said again, quieter this time. "Not just your memory, not just your service from the past, but your leadership today. Your kindness. Your belief that we are stronger together."

The memorial service was marked by the traditional 168 seconds of silence—one for each life lost. Names were read aloud, as they are each year, their echoes carried across the reflection pool that now rests where the Murrah Building once stood.

The Field of Empty Chairs shimmered in the sun, each one representing a soul taken too soon, each one a quiet reminder of the cost of hatred.

For many in attendance, Clinton’s return brought back memories of the first time he visited the site, just days after the bombing. Then, as now, he had offered more than political condolences. He had listened. He had wept. He had comforted.

Back in 1995, he told the families of the victims, "You have lost too much, but you have not lost everything. You have certainly not lost America, for we will stand with you for as many tomorrows as it takes."

Thirty years later, that promise still held. And yet, as Clinton spoke, there was a palpable sense that time had made the tragedy no less relevant. Extremism, the kind that led to the bombing, still exists.

Mistrust of government still fuels dangerous rhetoric. The machinery of disinformation has only become more powerful. That is what made Clinton’s speech more than an act of remembrance—it was a plea for prevention.

"There are forces at work trying to divide us again," said Sharon Willis, a retired teacher who lost her cousin in the attack. "We’ve been through this. We know where hate leads. President Clinton reminded us that the answer is not in shouting louder. It’s in listening. It’s in standing together."

For the people of Oklahoma City, the anniversary is never easy. Every April 19 is a return to grief. But it is also a reaffirmation of purpose. The Memorial Museum continues to educate new generations about the bombing.

Survivors and first responders continue to speak at schools and civic centers. The lessons of that day are not confined to history. They are warnings, and guides.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(903x251:905x253)/Bill-Clinton-Oklahoma-Bombing-041925-02-2a455400847f4b22bd7cc737eb3e89c8.jpg)

As the ceremony ended, church bells rang across the city. A wreath was placed at the Survivor Tree, an American elm that withstood the blast and has since become a symbol of hope and endurance.

Around its base, visitors left notes, flowers, and small tokens—silent gestures of remembrance. In the crowd, there were children holding photos of grandparents they never met. There were firefighters standing next to civilians.

Veterans standing beside teenagers. People of different races, faiths, and political beliefs standing shoulder to shoulder. They came not only to mourn, but to answer Clinton’s call.

"We need to hear that message right now," said Mark Jennings, a firefighter who responded to the bombing in 1995 and returned for the ceremony. "We’ve been drifting apart for too long. This reminds us who we are."

As the crowd slowly dispersed, the former president lingered, speaking with families, hugging old friends, and offering quiet words to those still processing loss. The sun was warm, but the air carried a certain solemn stillness. It was the kind of day that demanded reflection, and Clinton had provided the framework.

Unity, he had said, was not a luxury or a campaign slogan. It was a requirement for a nation that aspired to be better than its darkest moments. Thirty years ago, America watched as Oklahoma City turned tragedy into community. Today, that same spirit remains a blueprint for what the country can be, if it chooses to be.