Fifteen-year-olds in Hawaiʻi still can’t drive, vote, or buy alcohol—but they can legally marry, a fact that remains unchanged after a proposed ban on child marriage once again failed to pass in the state legislature.

Despite efforts by both national and local advocacy groups and growing national momentum to end child marriage in the United States, Hawaiʻi lawmakers for the seventh consecutive year declined to enact legislation that would raise the minimum age of marriage to 18 without exception.

House Bill 729, which would have outlawed all marriages involving minors, passed the state House of Representatives earlier this year with broad bipartisan support and backing from over two dozen sponsors.

It was backed by organizations such as the Hawaiʻi Commission on the Status of Women and local chapters of Zonta International, as well as national groups like the Tahirih Justice Center and Unchained At Last.

But once the measure reached the Senate, it hit a wall in the Health and Human Services Committee, chaired by Sen. Joy San Buenaventura, who declined to schedule a hearing. That procedural decision effectively killed the bill for the current session.

Under existing Hawaiʻi law, 16- and 17-year-olds may marry with parental consent, while youth as young as 15 can marry if they obtain judicial approval. The state has long maintained this legal structure, even as a growing number of states have moved to end child marriage outright.

Since 2018, thirteen states and Washington, D.C. have passed laws to prohibit marriage for anyone under 18, with no exceptions. Two more states—Maine and Missouri—have passed similar bans this year that await gubernatorial signatures.

Child marriage remains relatively rare in Hawaiʻi but not extinct. Between 2000 and 2022, more than 800 minors were married in the state, according to an analysis by Unchained At Last.

The vast majority—686 of them—were girls, and most married adult men. While many of these couples were close in age, some teens married adults significantly older—up to 21 years their senior.

Health department data submitted as legislative testimony described most underage marriages as “teens marrying teens,” yet the law sets no upper age limit for the adult spouse.

The analysis also revealed that child marriage in Hawaiʻi has been declining: from 2005 to 2014, there were 329 underage marriages among state residents; from 2015 through 2024, only 90 occurred. In a broader study of over 230,000 marriages between Hawaiʻi residents, only 216 involved minors.

Still, critics argue that even rare instances are too many. They say the practice creates legal and social dynamics that endanger children, especially girls. Alex Goyette, public policy manager for the Tahirih Justice Center, called the failure to ban the practice “a shame, first and foremost for the children of Hawaiʻi who remain in danger of child marriage and all the harm that comes along with it.”

National advocates like Fraidy Reiss, founder of Unchained At Last, have highlighted data showing child marriage can lead to diminished educational and financial outcomes, increased risk of abuse, and a higher likelihood of poverty.

Reiss, herself a survivor of a forced marriage, argued that allowing children to marry—often without proper safeguards—can trap them in abusive or exploitative situations.

In many states, minors lack the legal autonomy to leave home, access shelters, or even file for divorce without adult representation. Marriage can make things worse, she warned, especially if used as a tool by parents to offload responsibility or control their child’s behavior.

“It costs nothing. It harms no one. But it ends a human rights abuse,” Reiss said, referring to the growing number of states that have eliminated child marriage altogether.

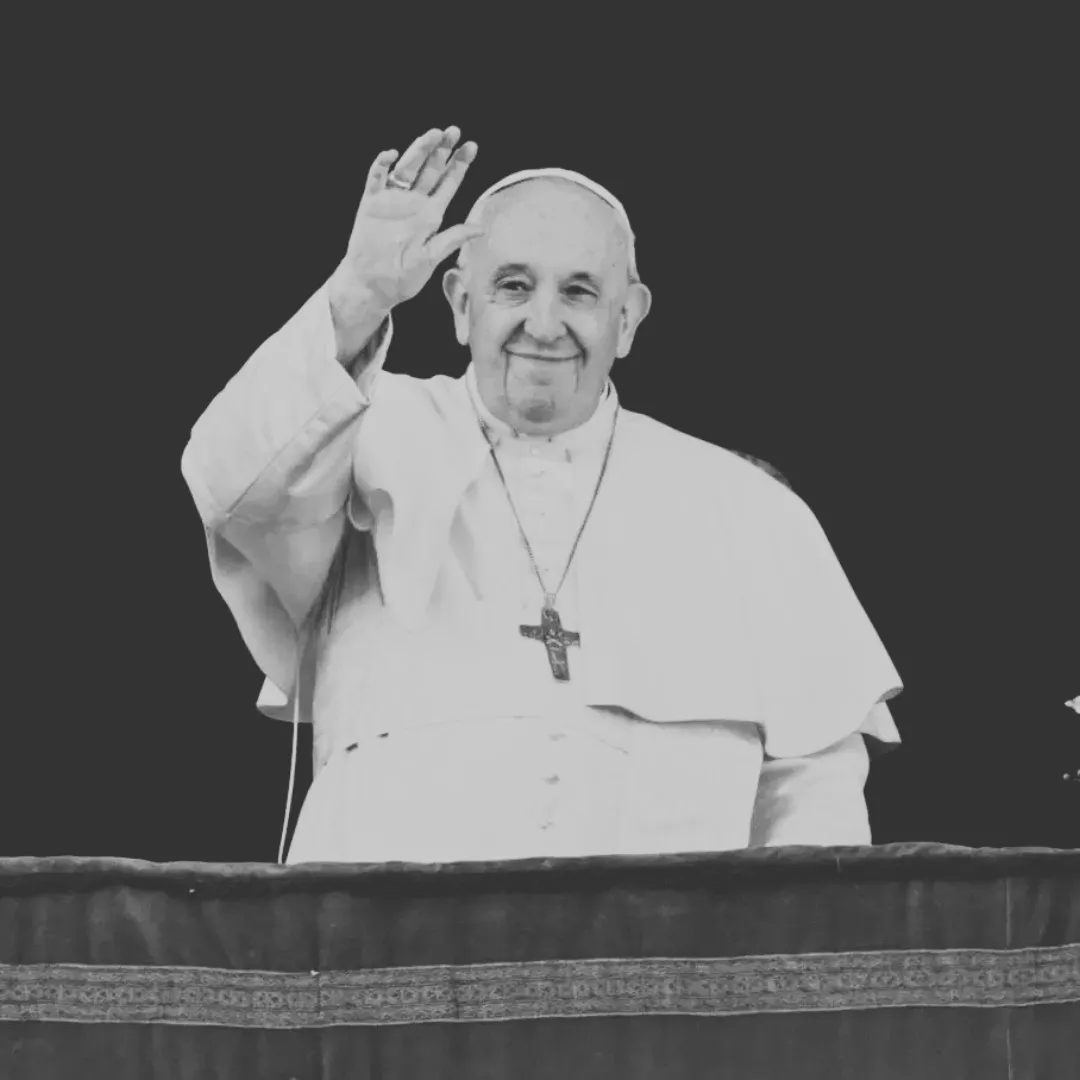

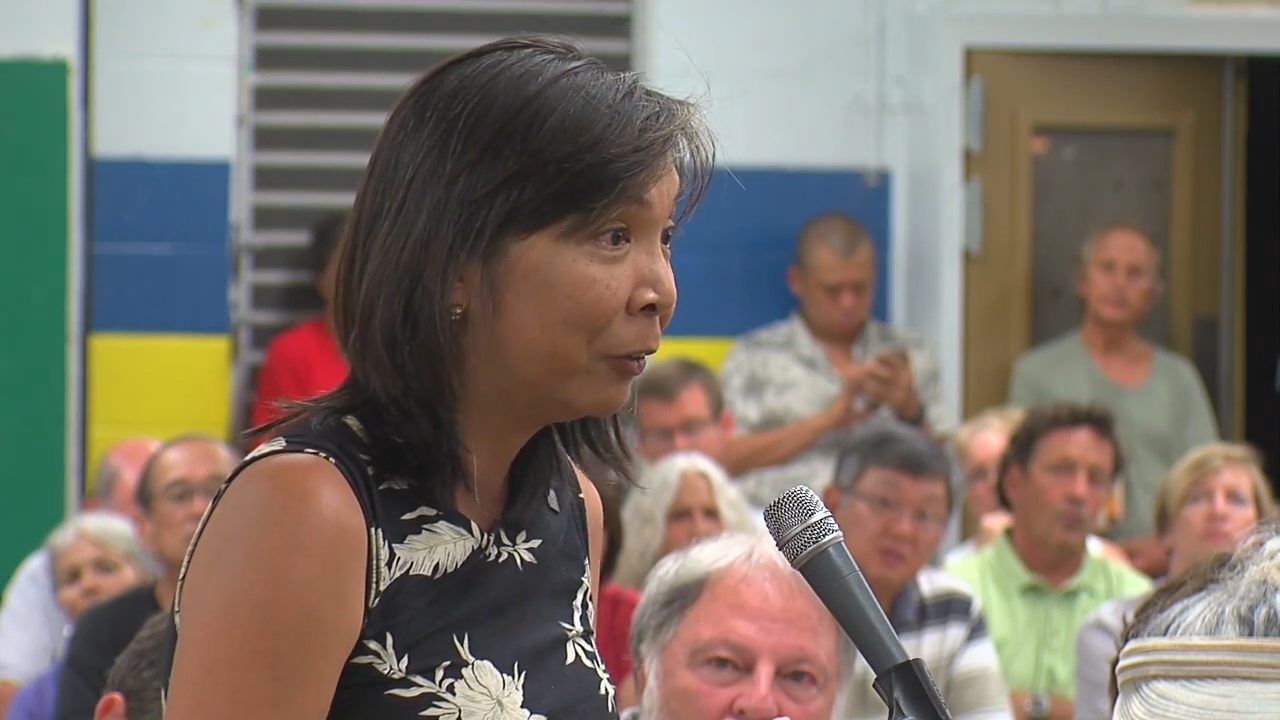

In Hawaiʻi’s case, supporters of the ban have run up against a persistent legislative obstacle in Senator San Buenaventura, who argues the issue is more complex than national groups suggest.

In an interview with Civil Beat, she defended her decision not to advance the bill, saying marriage can provide benefits to certain teenagers—especially those in difficult circumstances.

Before the passage of an emancipation law in 2024, she said, marriage was the only legal pathway for youth to gain adult status and access benefits like spousal health insurance.

San Buenaventura said she is wary of national campaigns that seek blanket bans without accounting for unique cultural or economic circumstances in Hawaiʻi.

“I am always leery of national advocacy groups who just want to notch Hawaiʻi as a win without taking into account the culture and circumstances here,” she said.

She cited cases in which teens might be pregnant, escaping abusive homes, or seeking independence, arguing that marriage offers a degree of legal protection not available through informal cohabitation.

“Why should the Legislature deny a pregnant teen health insurance or relegate her to taxpayer-paid health insurance just because a national advocacy group claims that she is better off cohabiting without marital benefits?” the senator asked.

She noted that in Hawaiʻi, where employers are required to provide health insurance, marriage can give teenagers access to private care that might not otherwise be available.

But advocates say such reasoning is dangerous. “Medicaid—not marriage,” Reiss countered, arguing that solving abuse or lack of resources through adult marriage is a policy failure, not a solution.

“The idea of telling a kid who’s in an abusive home, ‘Let’s get you out, just find you a husband,’” she said, “I mean, I grew up in an abusive home. I was forced to marry as a teen. That didn’t solve the problem. That’s just out of the frying pan, into the fire.”

Hawaiʻi’s recently passed emancipation law could render some of these arguments moot in future years, as it now provides an alternative legal pathway for minors to gain adult status and independence without getting married.

San Buenaventura herself acknowledged the shift, saying she now wants to see how the new law plays out before reconsidering legislation on marriage. Still, she maintains that marriage provides long-term legal protections—such as inheritance, property rights, and spousal support—that cohabitation does not.

One deeply personal story that illustrates the emotional complexity of child marriage in Hawaiʻi is that of Iris Lorenzo. At age 15, Iris was a high school sophomore at Kamehameha Schools when she met Edward “Bully” Lorenzo, a 21-year-old man who would soon become her husband.

Her mother, in poor health, encouraged the marriage to ensure her daughter had someone to care for her. Iris was soon pregnant, then again at 16, and again at 17. She managed to graduate high school, but the social cost was steep—her friends abandoned her, and she became isolated.

“That is the one thing that hurt me,” she said. Her marriage lasted nearly 50 years before Bully passed away in November. Still, Iris says she wouldn’t recommend that path to today’s youth. “I was basically ready to be an adult when I was 15,” she said. “But I look at my grandkids. No, they’re not ready.”

Advocates continue to press for change. They argue that even one minor at risk of abuse or coercion is too many, and that outdated marriage laws should not survive simply because they affect a small number of people.

“Even if 49 other states ban child marriage,” said Goyette of Tahirih, “all American kids are still vulnerable as long as a predator can buy a plane ticket to Hawaiʻi.”

The legislative session has ended, but the issue is far from resolved. With growing national momentum and renewed legal tools like emancipation laws now in place, pressure will likely intensify in 2025.

Advocates say they’re prepared to return again next year to push for a complete ban, hoping the state will finally bring its laws in line with what they consider basic protections for children.