A growing number of Southern Republican lawmakers are pushing for their states to officially adopt a new name for the body of water traditionally known as the Gulf of Mexico.

Following an endorsement by President Donald Trump, the name “Gulf of America” is gaining traction in statehouses across the region, with recent legislative and executive actions seeking to replace the long-standing name in textbooks, maps, official signage, and government records.

This week, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis signed two bills that require the use of “Gulf of America” in all state legal documents and school materials. Supporters of the measure say it’s a matter of national pride and cultural identity, arguing that the updated name reflects America’s strength and sovereignty.

Critics, however, have slammed the move as unnecessary, politically motivated, and potentially confusing for students and the public.

Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry earlier signed an executive order directing all state agencies to use the new term. His administration has already begun updating digital records and announced that public school social studies standards will be revised to reflect the change.

The Louisiana Department of Education confirmed this week that new materials adopted going forward will refer to the body of water as the “Gulf of America.”

In Alabama, the Republican-controlled House of Representatives passed similar legislation Thursday on a 72-26 vote, split largely along party lines. The bill mandates that all state and local government agencies, employees, and contractors use the name “Gulf of America” in official communications and public materials.

The law would also require government entities to make “reasonable efforts” to update signage, textbooks, maps, websites, and other resources to reflect the new name. It now moves to the Alabama Senate for consideration.

The sponsor of the Alabama bill, Representative David Standridge, said the legislation is about creating clarity and consistency. He said the use of “Gulf of America” stems directly from Trump’s endorsement and that state officials should align with that language.

“Right now, we have an executive order that the President issued,” Standridge said during floor debate. “This bill will make it clear, when you buy maps, when you buy textbooks, what to expect. We don’t want uncertainty. We want unity and pride in the names we use to describe our country.”

Standridge emphasized that the bill does not require existing materials to be discarded or replaced immediately. Instead, the law mandates that any new purchases made by schools, public offices, or local governments reflect the updated terminology.

“No one’s saying you need to go throw away all your old maps or rip pages out of textbooks,” Standridge said. “We’re just saying that from now on, if you’re buying new materials with public funds, they should use the name ‘Gulf of America.’”

While supporters describe the name change as symbolic and patriotic, Democrats have sharply criticized the effort, calling it a waste of time and resources. They argue that renaming a geographic feature known globally as the Gulf of Mexico serves no practical purpose and could cause confusion in education and international discourse.

“It’s time for us to stop doing foolish things, and start doing things that will move us forward,” said Representative Barbara Drummond, a Democrat from Mobile. “Our students need investment in science, literacy, and technology—not political messaging embedded in geography lessons.”

Democratic lawmakers also voiced concerns about the long-term implications of tying state standards to a naming decision made by a sitting president, especially in a time of shifting political landscapes. They questioned whether the name would remain if political power changes hands again at the federal level.

“Are we going to change the name back to the Gulf of Mexico if we get another president in another four years?” asked Representative Kenyatte Hassell, a Democrat. “Is this how we’re going to make public policy now—by chasing political slogans?”

Standridge responded that while a future president could theoretically issue a different directive, he believed such a reversal was unlikely.

“I really can’t myself imagine why a president would want to change from America to Mexico,” he said following the vote. “To me, that would be a step backward.”

Despite the partisan divide, the momentum behind the name change appears to be growing in Republican-led states. Several other Southern legislatures are reportedly considering similar proposals, and conservative media outlets have championed the rebranding as a cultural statement in support of American exceptionalism.

At the same time, the move has drawn national attention and sparked debate among historians, educators, and cartographers. Many experts point out that the term “Gulf of Mexico” has centuries of historical precedent and is used globally in maritime navigation, scientific research, and international law. Changing the name, they say, could create discrepancies and confusion in academic, legal, and diplomatic contexts.

One geography professor in Georgia expressed concern over the trend.

“This is a major waterway shared with multiple countries, including Mexico and Cuba,” she said. “It’s recognized internationally as the Gulf of Mexico. You can’t just decide on your own to rename it and expect the world to go along. This is performative politics, not sound cartography.”

In Florida, where the legislation has already been signed into law, school districts are beginning to plan for the rollout of new textbooks and learning materials that reflect the name “Gulf of America.” The state’s Department of Education issued a statement indicating that textbook publishers will be required to conform to the new naming standard if they wish to be included on the state’s approved curriculum list.

Some teachers have expressed hesitation, worried about confusing students or conflicting with federal or national standards, which still use the traditional name. Others have voiced concern about politicization creeping into science and geography education.

“I’m going to follow the law, but I worry about what we’re teaching students,” said a high school geography teacher in Pensacola. “They’re going to be tested on the Gulf of Mexico in national exams and the SAT. What are we supposed to tell them when the textbook says something different?”

Outside the classroom, reactions have been mixed among the public. Supporters of the name change say it sends a clear signal of pride and sovereignty, especially in Southern states that border the gulf.

“I love it. ‘Gulf of America’ just sounds better,” said one resident in Biloxi, Mississippi. “We should stop naming things after other countries when it’s our land and our water.”

Others, however, have questioned the motives and priorities behind the campaign.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/president-donald-trump-gulf-of-mexico-google-maps-012825-cf2eacee68e24a319eba5c182de4182e.jpg)

“With all the issues facing our state—education, healthcare, the economy—this is what they’re working on?” said a voter in Baton Rouge. “It’s embarrassing.”

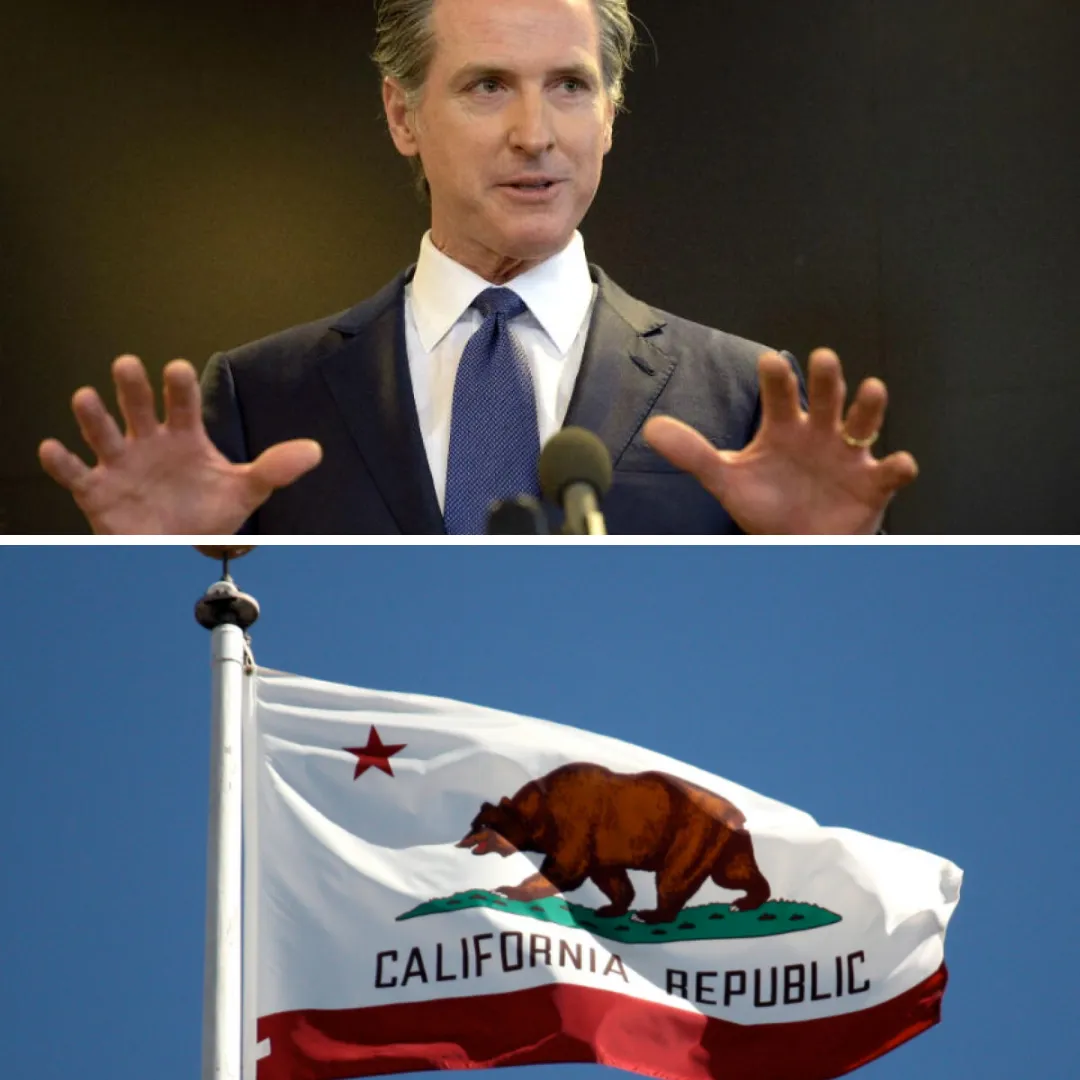

The name change effort is rooted in an executive order issued by President Trump earlier this year. In that order, Trump directed federal agencies to refer to the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America in official communications and encouraged state governments to do the same.

While the order does not carry legal force for states, Republican leaders have embraced it as part of a broader agenda to reshape cultural and political narratives.

Trump himself has spoken about the name on multiple occasions, framing it as part of his administration’s broader push to reassert American pride and identity.

“We’re not going to keep calling it the Gulf of Mexico when it borders our great American states,” he said during a rally. “It’s the Gulf of America now. That’s who we are. That’s where we live. And we’re proud of it.”

Whether the name will gain traction beyond Southern legislatures remains to be seen. National geographic authorities, including publishers of major maps and atlases, have so far not adopted the term. International bodies, such as the United Nations and global maritime organizations, also continue to use the traditional name.

Still, with Republican-led states actively codifying the change, the issue is likely to continue spreading both politically and culturally. Advocates are calling for businesses, tourism boards, and news organizations to adopt the new terminology. Merchandise using “Gulf of America” branding is already appearing online.

As lawmakers in Alabama prepare to take up the bill in the Senate, observers say it may pass along similar party lines. If it does, Alabama will join Florida and Louisiana in formally embracing the name.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/donald-trump-gulf-of-mexico-tout-010725-1ce1c143d7d84cd5a1ae184393847cbd.jpg)

For now, students, teachers, and government agencies across the region are left to navigate a changing linguistic landscape. As the political winds shift and the 2024 campaign season heats up, even the names of oceans and gulfs are no longer immune from partisan debate.